Wealth

Grumps: The life of the average person is getting worse.

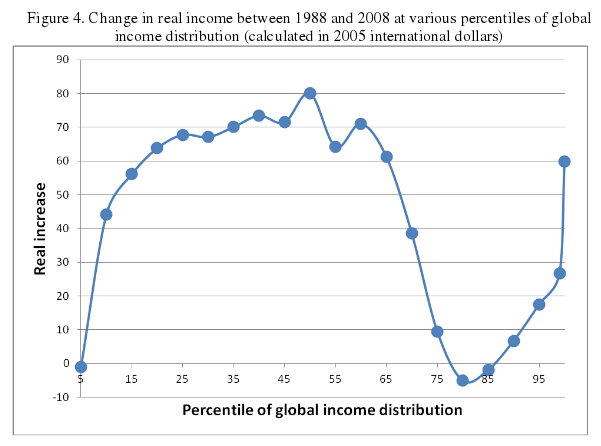

Optimist: The average person's wealth on the planet has been steadily increasing (inflation adjusted gross domestic product per person) 1:

Inequality

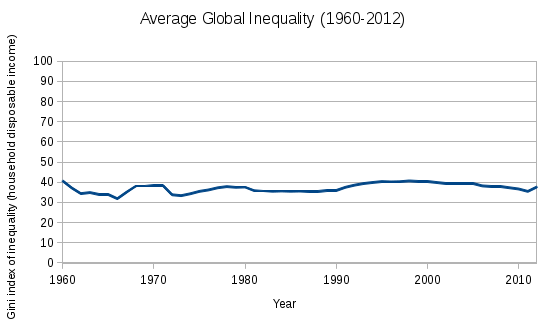

Grumps: Inequality is increasing.

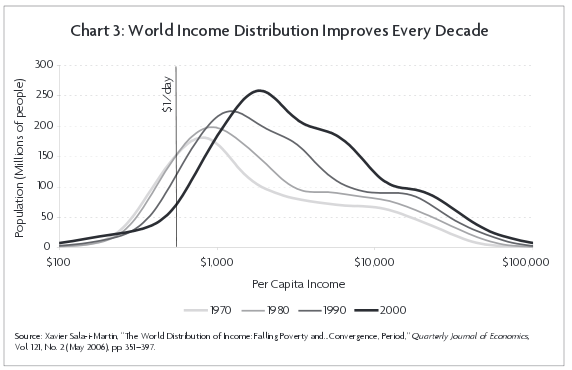

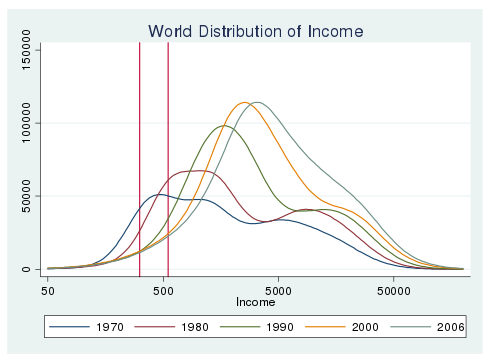

Optimist: Average global inequality is not increasing and is likely decreasing because poorer countries' falling inequality is offseting richer countries' rising inequality. 2:

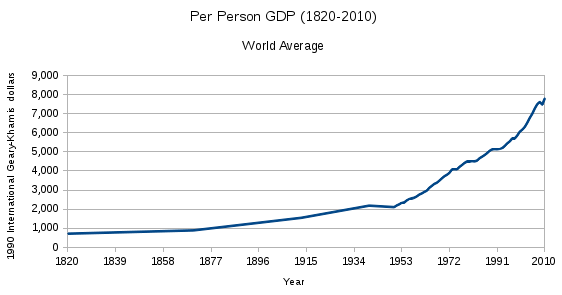

The paper presents an overview of calculations of global inequality, recently and over the long-run as well as main controversies and political and philosophical implications of the findings. It focuses in particular on the winners and losers of the most recent episode of globalization, from 1988 to 2008. It suggests that the period might have witnessed the first decline in global inequality between world citizens since the Industrial Revolution. 3

We estimate eight indexes of income inequality implied by our world distribution of income. All of them show reductions in global inequality during the 1980s and 1990s. 4

Using the official $1/day line, we estimate that world poverty rates have fallen by 80% from 0.268 in 1970 to 0.054 in 2006. The corresponding total number of poor has fallen from 403 million in 1970 to 152 million in 2006. Our estimates of the global poverty count in 2006 are much smaller than found by other researchers. We also find similar reductions in poverty if we use other poverty lines. We find that various measures of global inequality have declined substantially and measures of global welfare increased by somewhere between 128% and 145%. 5

Too Much Stuff

Grumps: Too many choices, such as at a supermarket, cause feelings of anxiety, guilt, and inadequacy.

Optimist: Research on choice overload is mixed, but the average result is that the amount of choice has no effect:

The choice overload hypothesis states that an increase in the number of options to choose from may lead to adverse consequences such as a decrease in the motivation to choose or the satisfaction with the finally chosen option... In a meta-analysis of 63 conditions from 50 published and unpublished experiments (N=5,036), we found a mean effect size of virtually zero but considerable variance between studies. 6

Modern Vapidity

Grumps: Modern economies can only satisfy primal needs while neglecting our deeper unhappiness.

Optimist: Nothing stops people from voluntarily exchanging with each other not just trinkets, but also wisdom, help, and experience. Perhaps we had to fulfill our basic needs before we could get to the bigger ones.

What we call ‘a business idea’ is at heart just an as yet unexplored need. To trace the future shape of Capitalism, we only have to think of all the needs we have that are, currently, poorly understood and neglected by the commercial world.

There’s no shortage: we need help in forming cohesive, interesting communities. We need help in bringing up children. We need help in calming down at key moments (the cost of our high anxiety and rage is appalling in aggregate). We require immense assistance in discovering our real talents in the workplace and understanding where we can best deploy them (a service in this area would matter a great deal more to us than pizza delivery). We have unfulfilled aesthetic desires. Elegant town centres, charming high streets and sweet villages are in desperately short supply and are therefore absurdly expensive – just as, prior to Henry Ford, cars existed but were very rare and only for the very rich.

These higher needs are not trivial or minor wants, little things we could easily survive without. They are, in many ways, absolutely central to our lives. We have simply accepted, without really thinking about it, that there is nothing we can do to address them. And yet to be able to structure businesses around these needs would be the commercial equivalent of the discovery of steam power or the invention of the electric light bulb. 7

Beneath their interest in profits, businesses are forced to engage with nothing less than the issue of how to satisfy their customers, a subject full of contradictions and complexities. For its part, philosophy has spent most of its long history investigating the ingredients of a good life, what Aristotle called eudaimonia, a Greek word translated as ‘flourishing’ or ‘fulfilment’. In their different ways, philosophy and business have to work out how to satisfy people – and therefore how they tick.

Most businesses outside a tiny crooked minority have to be committed to promoting the flourishing of their customers. Their long-term survival depends on it. Perhaps they’re selling people hand dryers or household insurance, but ultimately, their livelihoods depend on the accuracy with which they have discerned the true needs of those they have set out to serve: profit is the reward for working out the reality of your clients ahead of anyone else. In order to work through the psychology of their clients, businesses commonly rely on market research, carried out for them via focus groups and interviews. But they are typically not stepping back and properly thinking about human nature from a 2,000 year cultural perspective and their analyses of their customers suffer as a result. An ordinary businessman would ask: ‘How do I improve my margins in the ski business?’ But a philosopher would ask: ‘Where is the need to ski rooted in the human soul?’ Eventually the philosopher would find a way back to the balance sheet, but the starting point would be higher and broader and the results often more interesting. With a proper philosophical perspective on the needs of customers, businesses can start to see new market opportunities, rather than merely being left to fiddle with margins, wages and logistics. 8

The first thing we do in a gym is make diagnoses: we go to a different area to work on a different part of ourselves. This would be similar to the new Repton Park, but instead of thinking that we need to work on our biceps we might decide we need to work on our envy – or on our confidence, or frustration, or anxiety.

Around the gym we understand routine: we need to do the same thing many times to get results. We have developed some rather odd-looking but specially evolved exercises: movements with various barbells, a contraption so you can flex your lower back muscles, routines with the exercise ball. In the realm of the psyche there may be a similar set of odd-looking exercises, which we haven’t yet invented. There may be works of art you have to look at in certain ways, questions you have to ask yourself, texts to memorise, or situations to rehearse (being patient at the moments when you are irked; noting when you get defensive).

We might walk into a room of people being tested in mock frustrating conversations, or rehearsing moments to step down during domestic rows. Another area might invite us to work with a trainer to rehearse different types and ranges of speaking based on some scripts from recent films.

In a large climbing hall we might find people working in pairs on an obstacle course, practising giving urgent, complicated directions to one another in a kind way. And in another side room we might find people analysing recent instances of particularly stubborn anxieties which they have become aware of. 9

One would witness a surge in demand from the population at large for the services of people trained in culture in this new way – given that no one currently knows how to run a relationship, everyone is confused about bringing up kids, few of us have a clue how to manage our anxieties and death is universally terrifying.

The unemployment of arts graduates is shameful and unnecessary because culture has answers and highly useful consolations to the urgent dilemmas of real people. We just need to get these insights out, package them properly, and commercialise them adequately, so that the armies of people currently serving coffee can put their minds to proper use.

We aren't creatures who need only practical things like food and drink, cement and running shoes. We also desperately crave nourishment for what we might as well, with no superficial associations, call our souls. This soul-related work should become a huge and legitimate part of the world economy, worth as many billions as the cement trade. 10

Rich People

Grumps: Rich people are insatiable in their desire to acquire more and more.

Optimist: In some cases, this insatiable ambition can provide benefits for everyone, although it must not be allowed to run amock.

Ironically, the one thing the hard-working rich don’t actually want and are not in any way motivated by is money itself. They have far more than enough of that already and they know it. Their every material need is catered for (one can nowadays buy a comfortable life for a year using what they earn in a day). Nor – at this point in the history of civilisation – are the rich likely to be working for the sake of their children. There are too many examples of large fortunes that have driven kids insane with guilt for any modern plutocrat to be able to tell themselves that they are doing it for the next generation.

The rich are not, therefore, working to make more money with an eye to spending it. They are making money in order to be liked. They are doing so for the sake of status, as a way of keeping score and letting the world know of their value as human beings. The rich work for love and for honour. They stay up late at the office out of vanity – because they want to be able to walk into rooms full of strangers and be swiftly recognised by those that matter and deemed miraculous and clever for having made fortunes, whose size is carefully recorded by the media the world over.

In many cases, this works out well for everyone. There is often no conflict between the insatiable vanity of corporate chiefs and the requirements of society. That is one of the miracles of Capitalism, first observed by Adam Smith: the system can put personal selfishness to work for the public good. Capitalism doesn’t have to rely on kindness or virtue, which makes it infinitely more robust than rival economic arrangements, the kind that explicitly demand that those in charge have pure hearts (Communism). Under certain circumstances, corporations driven only by the profit motive can pass two key tests: they can treat their employees extremely well and they can produce excellent goods and services. Private vice can give rise to public virtue: companies can pay thousands of workers handsome salaries and fill shops across nations with wholesome necessary goods – and at the same time, the CEO’s at the helm may be deeply unpleasant, asocial and narcissistic types who pay not even one passing thought to the genuine needs of the societies they in fact serve so well.

That’s how it should work. But sadly, too often, it no longer does. Under the pressure of the raw profit motive, two things are happening: workers are increasingly abused (their salaries and conditions are reduced to an inhumane minimum) and the quality of products is grievously undermined (corners are cut, false claims are made, the best promises of the company are sacrificed). And paradoxically, all this unhappiness flows from one cause only: the need to continue filling the bank accounts of people who don’t – as we’ve learnt – truly even want money for its own sake, people who only want money to be loved.

Surveying the problems of Capitalism, the standard response of the left has been to suggest that one simply tax the rich more. But this fails to grasp, and therefore properly to exploit, the real psychological motives of the rich. The rich only pursue money fanatically (to our great collective cost) because wealth appears to be the primary, most objective source of honour in the modern world. If only we can fix how honour is obtained, we will be able to redirect their mania to more socially beneficial ends in ways that don’t demand that the rich become ‘nice’. 11

Perhaps a lot of the resentment against the rich is really a way of being justifiably angry, not at their money, but at their lack of purpose and imagination. Could a society evolve so that it paid attention not only to the opportunities for making money but also to the expectation that it be spent with equal intelligence and rigour? Arguments in favour of redistribution and against inequality are at least in part complaints about wasted opportunities. 12

Race to the Bottom

Grumps: Capitalists drive the relentless race to the bottom of product quality.

Optimist: The consumer has the ultimate decision making power over production, and as wealth increases, consumers can demand better quality, better work conditions, etc.

The people who run fast food companies don’t, in their cunning hearts, think that their offerings are ideal, or that the job opportunities they provide are humane. They are not driven by a fixed desire to cook rubbish or create repetitive, stressful low-paid employment. They just want, very badly, to make a profit, but they’d make it anywhere if they could. If we wanted to buy wild salmon or pay a little extra for staff medical insurance, they’d let us...

The problem isn’t what these businesses are offering, since an offer can always be politely declined; it’s what we are choosing. The reform of capitalism hinges on an odd-sounding, but critical task: the education of the consumer. 13

If their route to your table were dignified and ethical at every stage, lemons would of course cost a lot more. But maybe then we’d stop taking these fruits for granted and our appreciation of their zest would be all the keener. 14

Monday, Sep 04, 2017 8:19:13 PM